An unhappy marriage came to an early end in June when the government of the populist conservative PVV, liberal conservative VVD, the centrist NSC (founded by Pieter Omtzigt) and populist farmers’ party BBB collapsed over asylum policy. PVV subsequently withdrew from the coalition, followed by the NSC in August. This means that the current caretaker government of VVD and BBB only represents 32 out of 150 seats in parliament.

The economy would benefit from the new government tackling some thorny issues. Supply-side constraints continue to hinder potential growth, and clear direction and investment are needed. Budget-wise, short-term problems are small but structural overspending looms in the medium- to long-run. With the election less than two weeks away (29 October), we will look at the most relevant economic and budgetary policy issues, the latest polling, and explain why we do not expect significant political decisions in the months ahead

The economy could use clarity, reforms and investment from the next government to boost potential growth

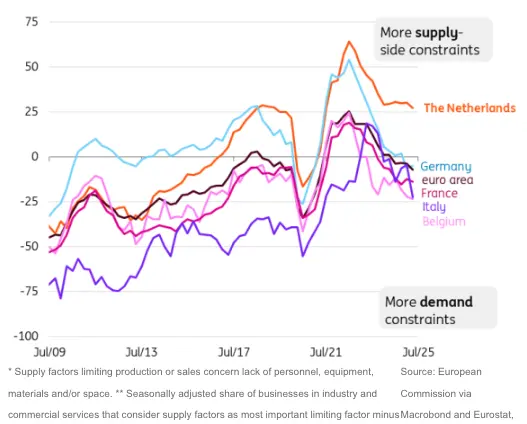

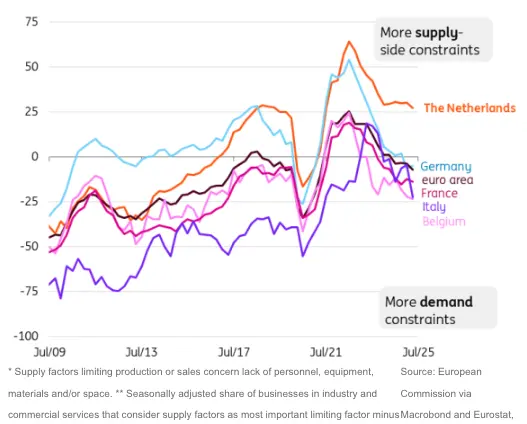

The Dutch economy has outperformed most European markets in recent years. A small technical recession after the energy crisis has not changed that picture very much. Unemployment is low and purchasing power has recovered from the inflation shock for most households. At the same time, supply-side problems are becoming more pressing. Labour shortages are more significant and structural than in most other European economies. But physical and environmental constraints also weigh on potential growth. Nitrogen emission space, scarcity of building permits and available land, limited capacity on the electricity grid and regulatory uncertainty have proven to be considerable hurdles to investment in the Dutch economy, which could become worse if the government leaves all of this untouched.

Dutch businesses experience relatively more supply constraints than businesses in peer economies

Degree to which supply side constraints* dominate demand constraints according to non-financial businesses with personnel in the private sector**

In an economy that is mainly constrained by supply, investments aimed at boosting productivity are important for future growth. The Netherlands has underspent on R&D, and public investment in general has been shrinking as a share of GDP. According to the OECD’s PISA programme, educational performance has also worsened. This limits the potential growth of the economy in the years ahead, despite the current strong performance.

But given this robust economic performance, it is unlikely that these supply-side issues will become a big theme in the elections. While most parties do emphasise the need to solve these problems in their election programmes, they don’t feature as the most important issues for the elections. The one exception is the housing market, which was mentioned as the number one topic by voters in a poll in July. Migration and health care were second and third.

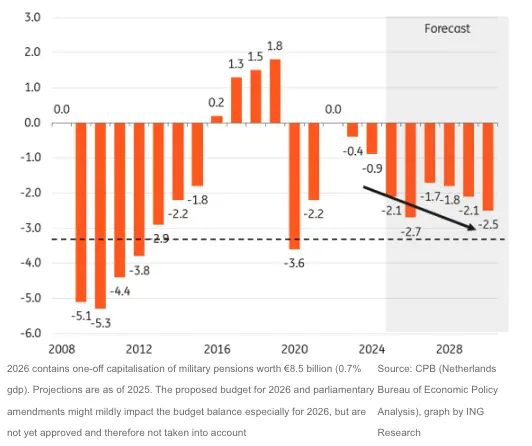

Budgetary challenges will be considerable for the next government, but from a comfortable position

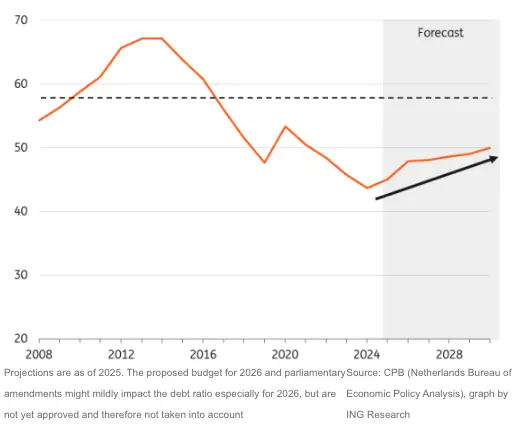

From a budgetary perspective, the Dutch situation is quite rosy compared to most other advanced nations. With a debt ratio of 43.7% of GDP and a budget deficit of -0.9% of GDP in 2024, the Netherlands is among the more prudent EU member states. So, there is no real cause for immediate concern. And even without major shifts by the new government, the favourable position compared to other countries is expected to hold, suggesting it is unlikely that the Netherlands will become a point of concern for financial markets.

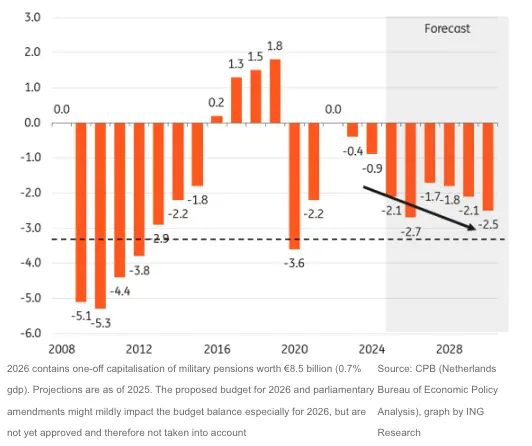

Then again, challenges do remain and caution about the development of the fiscal situation is warranted. The current budgetary position has benefited from underspending, as supply-side constraints have prevented planned government expenditures from materialising. And the next government will likely have to deal with disappointment as some large items currently in the budget seem overly optimistic and are unlikely materialise in full (e.g. cost savings on contributions to the EU budget and subsidies from the Recovery and Resilience Fund).

Increasing deficits, but still remaining within the 3% range for a number of years

Government budget balance of the Netherlands as % of GDP, projections by CPB**

Larger challenges do exist over the medium and long term, however. Projections show an emerging issue due to ageing, limited cost containment in health care and social security, and rising interest costs. Additional structural defence spending of 1.5% of GDP comes on top of that. An independent government advisory body of civil servants recommends that the next government start to address these issues, while the European Commission also highlights that nationally-financed net primary expenditures are already rising too fast.

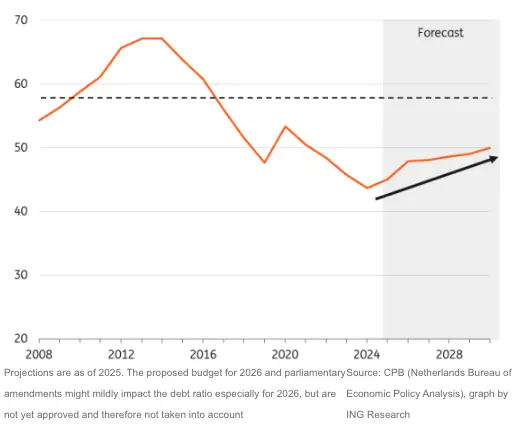

Dutch government debt low by global standards but expected to rise in the coming years

Government debt of the Netherlands as % of GDP, projections by CPB*

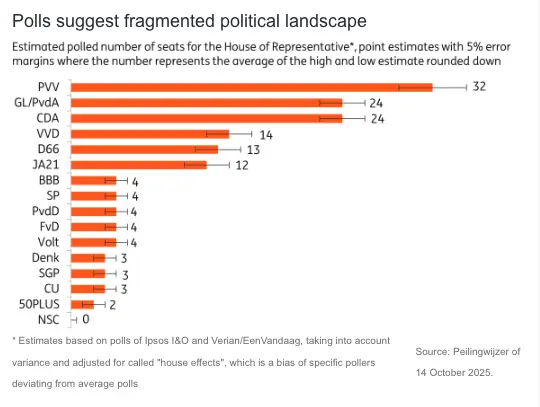

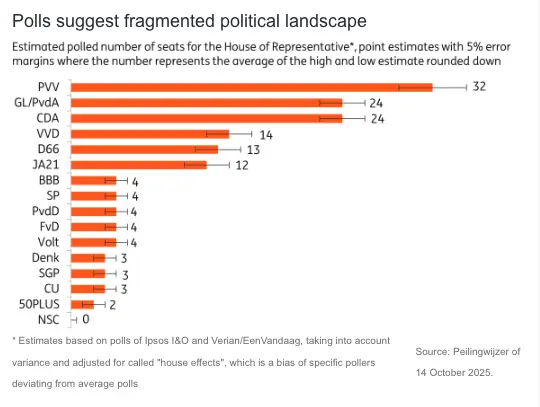

Polls suggest continued fragmentation

A common theme in European politics in past years has been fragmentation and the Dutch situation is no exception. No fewer than 15 parties are currently in Parliament and the polls show that the coming parliament will not be much different. The concentration of seats among the larger parties has dramatically declined in the most recent elections. This means that forming a government has become more of a struggle.

For the coming elections, populist conservative PVV led by Geert Wilders remains in the lead according to polls at the moment of writing. But most other parties have ruled out forming a government with the PVV at this point, which makes it less likely that the PVV will be part of the next coalition. What is left is a very fragmented landscape, which means that a broad coalition of more than three parties will likely be necessary for a majority government to be formed. As things stand now, a four-party majority government would only be feasible with the social democrats/progressive green left (PvdA-GL), social liberals (D66), Christian democrats (CDA) and the conservative liberals (VVD). A majority could come by a very slim margin. Currently, an alternative combination of four parties including conservatives (JA21) lacks one seat for a majority.

There is, of course, the possibility of including other (smaller) parties for specific policy proposals and/or a larger majority, but this could make negotiations and managing the government more challenging. A minority cabinet would also be a possibility, but so far there is not much appetite for such an arrangement.

Significant compromise required in terms of budget composition

Looking at the possibilities of a majority government shows that there is a world of difference in terms of their preferred composition of the government budget, but less so when it comes to the degree of fiscal prudence. All of the major parties in the polls except PVV have presented their plans to the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (CPB), which has modelled the economic outcomes of the plans. These parties all want to increase defence spending significantly. Except for JA21, all of them want to stay within the 3% of GDP budget deficit in the coming term. So, we don’t expect the Netherlands to use the exception to the EU Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) for defence spending.

Differences between parties over how to incorporate increased defence spending into the budget are more pronounced. Total government expenditures go up substantially over time for almost all parties, although for a few parties this is caused by rising costs resulting from the base case of existing policies. Left-leaning parties opt for defence spending on top of current spending, with taxation also increasing. Right-leaning parties make cuts to spending that more than compensate for the additional defence spending and lower taxation compared to the baseline. Cuts are expected mainly in healthcare, while social spending and international development support are also cut back in several party’s plans.

For almost all parties, tax revenues still go up over time, even if only marginally in some cases. Under the surface, there are differences: more left-leaning parties propose increased taxes for businesses, environmental taxes and taxes on financial and housing wealth, while proposing substantially lower taxes on labour income. Right-leaning parties in general propose tax cuts across the board, albeit not in all cases substantially. Overall, this means that significant compromise will be required on the budgetary front for the next government.

So for markets, expect the Dutch government to remain quite prudent in the short run. But then again, the structural budget deficit remains a concern for the longer term. Of the largest six parties in the polls, only VVD and JA21 improve the structural state of public finances, while in all manifestos the projected government debt will surpass 100% by 2060. Given the history of prudent government finances in The Netherlands, we see this mostly as implying that additional political pain will have to be taken over time to deal with the impact of ageing and defence spending