However, concentration can be justified if the asset’s volatility or correlation to other assets in the portfolio is low, or the return outlook is high. Concentration is the opposite of diversification.

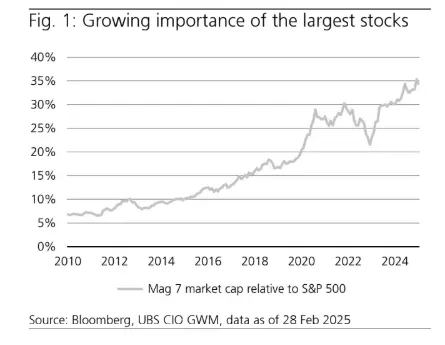

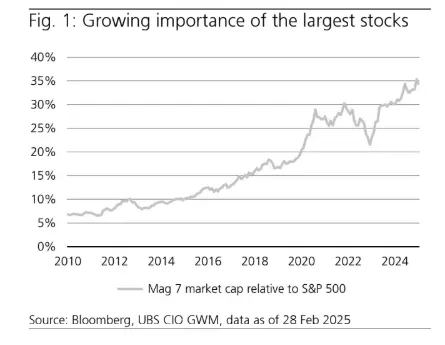

In recent years, the significant outperformance of the “Magnificent Seven” stocks has lifted their combined weight to roughly 35% of the US stock market. This concentration has raised concerns that the US equity market may be overly dependent on a handful of names. Additionally, the US now represents over 70% of the global developed equity market weight.

Despite these figures, when comparing the largest US stocks or sector composition to other markets, the US is not an outlier. Also, the market’s relatively low volatility supports a higher market weight. And if the US continues to outperform, investors may be less inclined to question the impact of concentration.

Rising concentration

It is the well-established wisdom of modern portfolio management that by diversifying across individual stocks, countries and assets, investors can achieve the same return with lower risk, or higher returns for the same risk. This is often summarized in the universal conviction that ‘diversification is the only free lunch in finance’.

Nevertheless, over the last decade financial markets have become more concentrated and less diversified. For example, concentration has been rising in equity markets; large stocks have been getting larger and the US, the dominant equity market, has become more dominant. Should investors worry? On the following pages, we describe the main effects of portfolio concentration and when investors should accept or mitigate concentration. We will ask how an individual investor should judge the concentration in his portfolio and how this assessment depends on the portfolio context, his home bias and on the investor’s ability to forecast financial markets.

Measures of concentration

There is no single universally accepted measure for concentration in portfolios. When evaluating stocks, the "concentration ratio" is often used. This ratio considers the combined weight of the top assets in a portfolio, such as the size of the largest, the three largest, or ten largest stocks.

However, the size of a position can be an imperfect indicator for the risk of such a stock position. To better understand the origin of risk, it is useful to distinguish between common and firm-specific drivers of companies’ success. Common factors that affect most stocks include for example recessions that results in a broad decline in demand for goods, a country-wide drop in real estate prices that has a significant negative wealth effect, or higher energy costs, tariffs, etc..

On the other hand, company-specific incidents could arise from mis-investment, fraud, reputational risk, product failures...

Normally it is the company-specific risks that cause concern over concentrated positions, because they become unnecessarily impactful. For example, when owning only one stock, the stock-specific risk has full impact, but obviously such a single stock-specific risk is less impactful if the portfolio consists of several stock. Also, if a company spins off parts of its business, stock-specific risk declines.

When looking at portfolios with different asset classes, concentration measured based on weights are difficult to compare. For example, a single bond with a weight of 30% is normally significantly less risky than a 30% single stock position.

Therefore, we suggest to not look at the concentration in weights but consider the concentration of risk. This can be captured with the diversification ratio, which is the sum of the assets' volatility divided by the portfolio volatility. If the ratio is close to 1, the portfolio is highly concentrated. The ratio increases as concentration decreases and diversification increases.

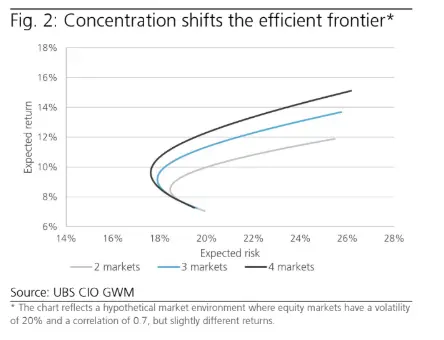

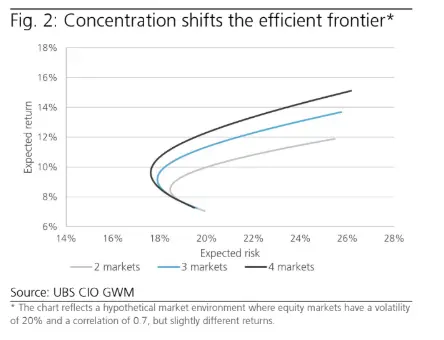

Consequences of concentration Concentration typically reduces portfolio efficiency, as concentrated positions inherently challenge the benefits of diversification. For example, a portfolio invested in a small number of markets, moves the efficient frontier into more unfavorable territory.

Concentration can be measured and assessed at various levels of a portfolio: the single security level, which covers the characteristics of instrument allocation within a market; the market level, which covers the characteristics of market allocation within an asset class; and finally, the asset class level, which covers the allocation of asset classes in a global portfolio. The effects are similar, but sensitivities depend on characteristics, like volatilities or correlations.

We illustrate the effects at the single security level by analyzing stocks. The market level is illustrated by investigating the characteristics of the global equity market and the related country or sector allocation. The approach presented could be extended to bonds and the asset class level, but for this report, we’ll focus on stock and market selection.