Gold’s Meteoric Rise: Forecasts, Central Bank Buying, and Market Risks

As gold broke above $3,000/toz on March 14, we address the most frequently asked questions on the outlook for gold.

As gold broke above $3,000/toz on March 14, we address the most frequently asked questions on the outlook for gold.

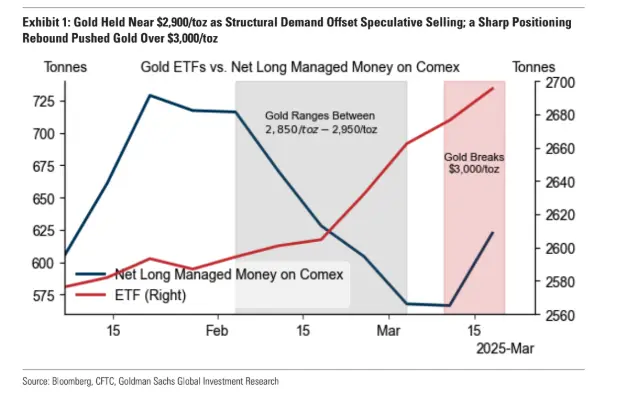

Gold broke above $3,000/toz following a sharp rebound in speculative positioning. In the weeks prior, gold had traded around $2,900/toz despite steady liquidation from speculators on Comex, likely driven in part by broader equity market weakness and associated margin calls. Over the span of 6 weeks, speculative length declined by 150 tonnes, yet prices remained supported by structural demand, including a notable pickup in gold ETF inflows (~80 tonnes) and what we estimate to be ongoing central bank buying amid rising US policy uncertainty (Exhibit 1).

The catalysts for the breakout above $3,000/toz included headlines about a possible tariff package targeting the EU and increased media attention around a so-called “Mar-a-Lago accord” framework (see Q4) causing speculative positioning to rebound, rising back to the 85th percentile (vs. percentile 79 in the week prior), with net additions of ~60 tonnes.

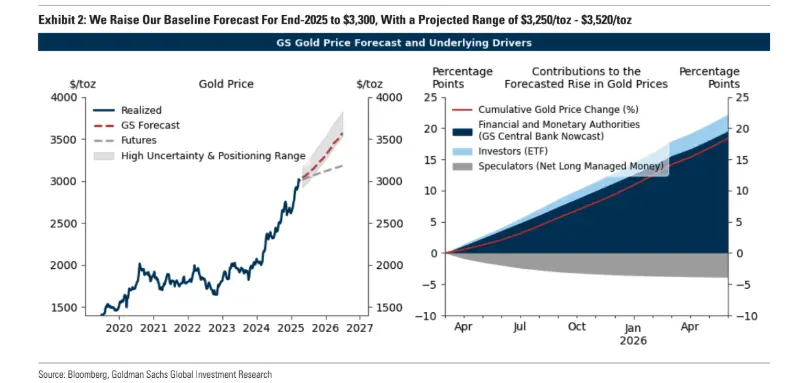

We raise our baseline forecast for end-2025 to $3,300 (vs. $3,100 prior), with a forecast range of $3,250-$3,520 (vs. $3,100-3,300 prior). This upgrade reflects the recent upside surprises in ETF inflows and stronger central bank demand (Exhibit 2). Our base case assumes that speculative positioning normalizes from current elevated levels (85th percentile), while the top end of the range reflects scenarios where elevated uncertainty could keep positioning elevated or prompt further surges.

On the central bank side, we raise our demand assumption to an average of 70 tonnes/month (from 50 tonnes previously) for two reasons. First, our central bank nowcast shows a pickup in purchases since November amid heightened US policy uncertainty to a November-January average of 109 tonnes.1 Second, we estimate that large buyers— particularly China—may continue accumulating at a rapid pace for another 3-6 years to reach our estimated range of potential gold reserve allocation targets (see Question 3). Our revised assumption is well above the pre-2022 average of 17 tonnes/month, but modestly below the post-2022 average of 85 tonnes/month.

On the gold ETF side, our US economists continue to expect two 25bp Fed cuts in 2025 and one additional cut in H1 2026, which underpins our baseline for ETF inflows. That said, recent flows have surprised to the upside, likely reflecting renewed investor hedging demand. While ETF flows generally track Fed policy rates, history shows they can overshoot during extended periods of macro uncertainty — such as during the Covid-19 pandemic. We explore gold price scenarios for further upside in ETF flows in Question 10.

Yes. Central banks—particularly in emerging markets—have increased gold purchases roughly fivefold since 2022, following the freezing of Russian reserves. We view this as a structural shift in reserve management behavior, and we do not expect a near-term reversal. Our base case assumes that the current trend in official sector accumulation continues for another three years.

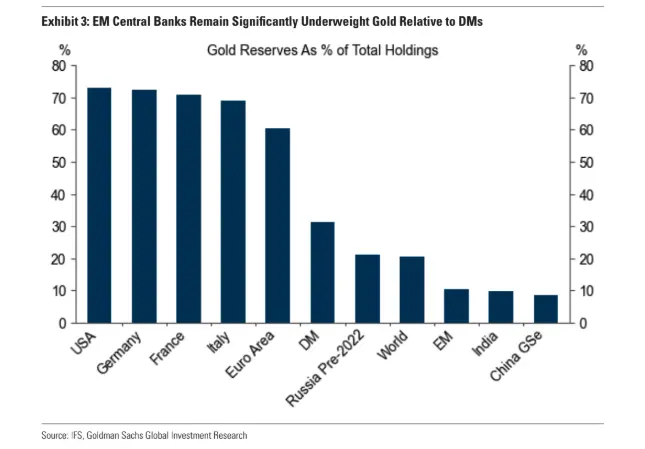

Our rationale is that EM central banks remain significantly underweight gold compared to their DM counterparts and are gradually increasing allocations as part of a broader diversification strategy.2 For example, we estimate that China—the largest buyer— holds around 8% of its reserves in gold,3 compared to ~70% for the US, Germany, France, and Italy. The global average is roughly 20%, which we view as a plausible medium-term target for large EM central banks, based on historical precedent and current positioning. For instance, Russia increased its gold share from 8% to 20% between 2014 and 2020, and repatriated its gold holdings ahead of sanctions.

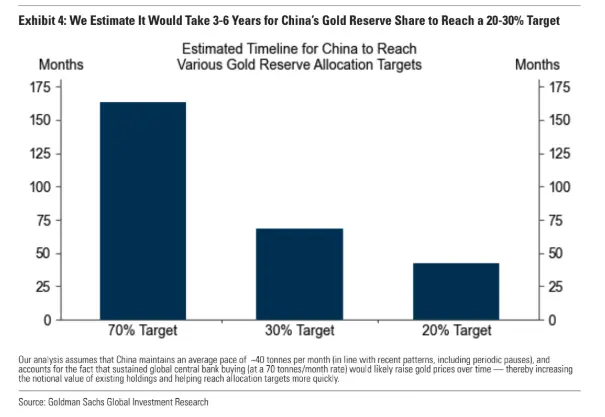

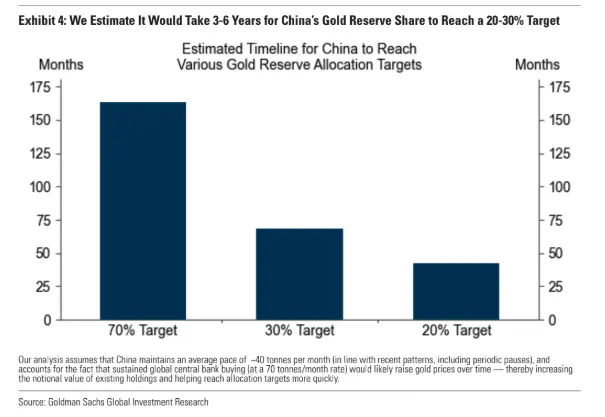

If the largest official buyer—China —were targeting an allocation of 20%, and maintained an average pace of ~40 tonnes per month5 (in line with recent patterns), we estimate it would take approximately three years to reach a 20% gold share. Our estimate also accounts for the fact that sustained global central bank buying would likely raise gold prices over time — thereby increasing the notional value of existing holdings and helping reach allocation targets more quickly (see appendix for details). Higher targets — such as 30%, closer to the DM average— would take roughly six years. A move to 70% (in line with large DMs whose gold holdings are legacy positions from the gold standard era) appears highly unlikely in our view, and would take 15 years.

The central claim is that the US dollar is persistently overvalued from the perspective of international trade models because of price-insensitive demand for US financial assets, particularly Treasuries, as the dollar is the world’s primary reserve currency.6 According to the note, this persistent overvaluation makes US exports less competitive, increases US import dependence, and handicaps US manufacturing. The note characterizes the associated reliance on foreign supply chains as a source of vulnerability to national security.

To address these imbalances, the note discusses both tariff and currency policy tools.

The note reviews the potential objectives of US tariffs, including rebalancing trade flows, reshoring of supply chains, boosting manufacturing, raising tax revenues, and enhancing leverage in negotiations, and how dollar appreciation in response to tariffs may impact on the trade balance and the boost to US consumer prices.

The note then outlines both multilateral and unilateral policy tools to potentially address dollar overvaluation.

On the multilateral side, Miran summarizes a proposal from Zoltan Pozsar to ask foreign countries to sell their US Treasury bill reserves while increasing the maturity (i.e. “terming out”) of the remaining reserve holdings to limit the upward pressure on long-term US yields. Miran argues that US trading and security partners may agree to this increase in interest rate risk in exchange for ongoing access to the US defense umbrella and a potential reduction in US tariffs as part of a broader cost-sharing arrangement. Our market strategists are skeptical of a centrally-planned currency accord, in part because, unlike in the 70s and 80s, the market today is not centrally controlled, and because private capital dictates the Dollar’s direction.

On the unilateral side, the report lays out two options. The first option is to impose a “user fee” on interest payments for new Treasury issuance on foreign official holders of Treasuries. Miran recognizes that a user fee may cause a spike in interest rates, and discusses mitigating these risks via a gradual phase in, targeting the fee to adversaries, and securing the voluntary cooperation from the Fed. The second option is for the US to start accumulating foreign exchange reserves.

Overall, while it is certainly possible for the Administration to take actions that erode the reserve currency status of Dollar assets, the market disruptions wrought by some of these policies could be large, and our market strategists therefore think that these are low probability tail risks and are skeptical about the implementation of these policies.

That said, market participants’ focus on these policy risks underscores the hedging value of gold against a potential growing market focus on US policy tail risks. Taking a step back, central banks have historically increased gold holdings to hedge geopolitical risks (i.e. the risks of financial sanctions) and to hedge financial risks (e.g. concerns about US fiscal sustainability). The geopolitical hedging motive has gained relevance since the freezing of the Russian central bank assets in 2022. The financial hedging motive may become more prominent if market participants were to raise their assessment of the tail probability of changes to US reserve management practices.